By Pierre Igoa —

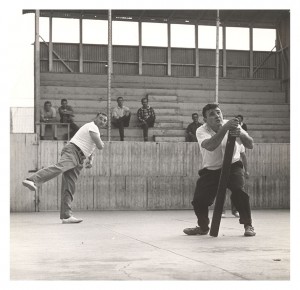

Handball player Jean Lorda; score keeper Jeannot Arrayet playing handball at Noriega Hotel

I’ll never forget that Sunday afternoon at the handball court at the Noriega Hotel.

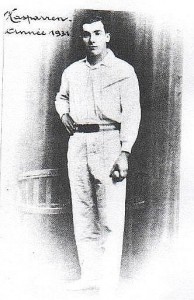

I was an impressionable teenager and had often heard my father speak of the exploits of legendary players such as Perkain, Gaskoina and Chiquito de Cambo.

Little did I know what awaited at the hotel’s trinqueta-style court. I was to be introduced to the personalities that made the game not only an exciting sport but a virtual celebrity event in Bakersfield and across the Basque communities of the western United States.

On this afternoon after church, with a satisfied stomach from a superb lunch prepared in Mrs. Elizalde’s Noriega kitchen, we gathered in the wooden stands behind the court. An older man (old enough to be anyone’s grandfather) sat in anticipation of the games. Sporting an interesting western hat, he rolled his own cigarettes and carefully licked the paper with the steady coordination of hand and mouth. Judging by his tobacco-stained hands and leathery skin, he had been doing this for many years. After a friendly exchange with a fellow spectator, each pulled out some money, handed it to a third person, shook hands and made a wager on the outcome.

As people filled the bleachers, a woman with a personality as colorful as her wardrobe made her entrance. Wearing more jewelry than all the other women combined, this “grande dame” of the game announced in a velvety voice her favorite player.

“Come on… Blue Boy!”she yelled out. I followed her gaze to see the image of a young dark-haired handball player with a blue cinta, or cloth belt. Beñat Arduain held his head high as he prepared for the match, bouncing the ball on the court with alternating hands. The name Blue Boy, coincidentally the name of a famous 18th century painting, was to be Benji’s name on the court. A quick look across the cross revealed his partner, also sporting a blue belt. His partner was altogether different though. He paced the handball court, hands on his hips, breathing deeply and rhythmically as he maintained a steely cold gaze at an imaginary point above the bleachers. He looked like Yul Brenner with an intensity of concentration like no one on the court. Like all great athletes, he was focused and seemed to be in a trance.

Sauveur Bidart, handball player. Note: Sauveur Bidart and Jose Recondo were honored at a Saturday, May 10, 1975 dinner at Noriega Hotel as winners of 1975 Kern County Basque Club handball tounament division I winners. Also honored were division II champs, Emile Arraztoa and Esteban Goni and winners of division III, Albert Falxa and Pete Ermingarat. It was the 5th annual event. Source: Bakersfield Californian – Friday, May 9, 1975

I soon learned by listening to my mother and father’s conversation that this was my father’s cousin, Sauveur Bidart. As the players squared off, I remember how emotions ran high on the court as well as in the stands. People yelled their approval and sometimes their disappointment after each point. The scorekeeper held a wooden palette as he announced the score in a semi-musical voice. With increasing anxiety, the oldest spectator rolled more and more cigarettes and smoked them until he could no longer hold them between his lips. The colorful woman, jewelry chiming in the wind, yelled with added enthusiasm, “OK Blue Boy!”

In the midst of all the hoopla, the most memorable actions that day were those of Sauveur’s. He celebrated points by keeping a stiff upper lip. During long exchanges with his opponents, he would pump his arm in excitement like Tiger Woods. In stark comparison during a lost point or fault of his own, he would markedly show his disapproval.

This was the most entertaining of moments. Sauveur would vocalize his disappointment, discuss the point with himself or oftentimes give the audience an instant replay of how the point should have been played. On some occasions he would replay the point with his head. This was the sign of how deeply he wanted to win the game.

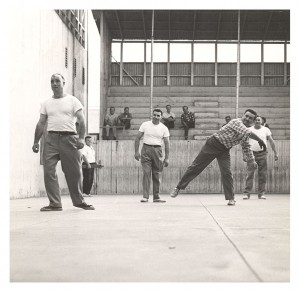

Physically he was not an ordinary athlete. He was not a large man by any means. This is what made him such a great player. He was the quickest the Bakersfield crowd had seen and perhaps will ever see. Playing a clever game, his opponents were careful not to allow him to control the game in the front court. If allowed the opportunity, Sauveur would make the competition run the court in pursuit of his finely placed pilota. Their best bet was to keep the ball away from Sauveur. But this was not an easy task since Blue Boy Benji was equally as adept playing the back court. The two played an awesome game. On the Noriega court, Sauveur displayed his all-around game and athletic style. And the crowd loved it.

People had been coming out to see the players for many decades at Noriega’s. Players that had previously graced the court with their presence were much larger players such as Pete Ermigarat, Frank Pedeflous, Jean Lorda, Pete Borda, Jean Errassarett and Jean Arrayet.

Handball players Michel Laxague and JP Palla playing handball at Noriega Hotel

In 1972, the Kern County Basque Club decided to buy a property with a clubhouse and build a handball court. There was an enthusiasm for the game and a growing need to build a court that the club could call its own. In August 1974, the Union Avenue property was purchased. Rainbow Gardens as it was called, was acquired for $60,000.

Later the dream of our own handball court would become a reality. Many great handball players and supporters of the sport were active during this time; Amedée Irey and Joxe Recondo as well as John (Pampi) Urrutia, Marcel Membrede, Henri Duhart and of course, Bernard Arduain and Sauveur Bidart to name a few.

With the talk of a new mur à gauche (left-handed wall court) came an increase in club membership. New members rushed in to help the club with the creation of a handball court that to this day pays tribute to the popularity of the game. A large sum of money even in today’s dollars, $40,000, was gathered through loans, donations and IOUs to build the court.

The “Gure Amentsa” (our dream) court was completed in 1978 with the court’s inauguration shortly following in November of the same year. The picnic that year was celebrated at Sacred Heart Church in Greenfield just outside of Bakersfield and then festivities were moved to the club’s new court for a handball match between doubles teams Ganix Iriartborde & Frank Pedeflous against Augustin Artechea & Pete Etchegoinberry.

During the summer of 1978, a delegation of handball players traveled to France from Bakersfield to represent the Basque club to compete in the World Championships. Before the completion of the Gure Amentsa court, Sauveur Bidart traveled to the nearest trinqueta court in Los Angeles to prepare for the competitions. His efforts paid off since he was the only one to get a bronze medal.

Although my cousin Sauveur was only here a short time to enjoy it, I can still recall the excitement that playing on the Gure Amentsa gave him. Sauveur would say that the Basques of Bakersfield, young and old alike, would finally have a handball court they could call their own.

Gaskoina or Kaskoina, as he was known, was born Jean Erratchun in Hasparren (Hazparne, Lapurdi) in 1817. Gaskoina was 42 years old when he died in 1859. He was a legendary figure whose most famous match, winner of the Title of Irun, which he won in 1846, has been immortalized in both song and prose.